A scoping review uses a systematic search strategy to gives a broad overview of a field of research or topic. Unlike systematic reviews with (or without) meta-analysis (SRMA), which are driven by a specific, well-defined research question typically structured around a Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome (PICO) framework, scoping reviews are designed to identify gaps in the literature, provide a broad overview of a body of literature, and pinpoint areas for future research. They are particularly useful at the early stages of a research program.

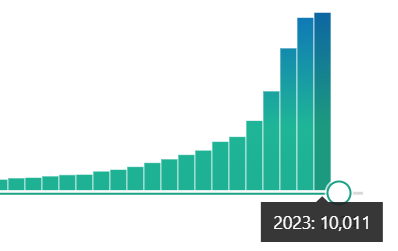

The rise of scoping reviews

Just using a simple PubMed search for ‘Scoping Review’’ we can see a rapidly increasing number of scoping reviews being performed each year.

This is a bit of a double edge sword – if used appropriately, scoping reviews are a great way to provide a broad overview of a field, identify areas for future research, or even identify specific PICO questions that would be amenable to systematic reviews (SRs). Unfortunately, some researchers perform scoping reviews as a way of avoiding some of the challenging and time-consuming aspects of systematic reviews like assessing for risk of bias, pooling effect estimates, and producing statements surrounding the certainty of evidence. So what is the difference between a scoping review and systematic review?

Differences between scoping reviews and systematic reviews

Lets compare and contrast core components of systematic and scoping reviews.

1. Search Strategy: Both scoping reviews and SRs utilize a systematic and repeatable search strategy. However, the search in a scoping review tends to be broader. This is because scoping reviews aim to map the existing literature on a topic without the constraints of a specific PICO question. For example, scoping reviews may include case reports, case series, translational studies, or even animal studies that might be excluded in SRs.

2. Evidence Synthesis: In a scoping review, the synthesis of evidence is narrative, and is really just a description of the included studies, without attempts to pool effect estimates. This approach allows for the inclusion of a wide range of study designs and methodologies. Unlike SRMAs, scoping reviews do not attempt to pool quantitative estimates from different studies, as the focus is on identifying and mapping the available literature rather than assessing the effects of a test or intervention.

3. Risk of Bias Assessment: Scoping reviews do not typically include a risk of bias assessment. This is because they are not focused on evaluating the extent to which individual studies contribute to an overall evidence base, as seen in SRMAs. The goal is to provide an overview of what is known about a topic, not to assess the certainty of evidence.

4. GRADE Recommendations: Scoping reviews do not produce a GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) level of evidence certainty. The aim is not to provide a graded assessment of the quality of evidence but rather to offer an exploratory and descriptive overview of the existing literature.

5. Level of evidence they produce: if used correctly, scoping reviews can be very valuable, particularly for new and developing fields of research. With that said, unlike SRMAs that are at or near the top of the evidence pyramid, scoping reviews do not typically generate authoritative evidence. This is because scoping reviews lack risk of bias assessments, pooling of estimates, and statements surrounding the quality and certainty of evidence.

When to perform a scoping review

So when should you perform a scoping review? In general, scoping reviews are invaluable in the early stages of programs of research to help identify gaps in the existing literature, and set directions for future inquiry. They are particularly beneficial in new or complex areas where comprehensive, high-quality evidence is not yet available. However, their utility is more limited in well-established fields where robust evidence already exists (e.g. multiple RCTs). By understanding the distinct purpose and methodology of scoping reviews, researchers can effectively utilize them to inform research strategies.

Finally, when you are designing a scoping review, check the PRISMA-SCr reporting guidelines for best practice items to include. Also, check out our recent scoping review on critical care transesophageal echocardiography to get an idea about the structure and focus of a scoping review.