Not all diagnostic accuracy studies are created equal. The diagnostic test accuracy sub-designs of ‘Cohort’ and ‘Case-control’ have significant impact on the diagnostic accuracy estimates. Here’s how to avoid overestimating the accuracy of diagnostic tests in clinical practice.

Cohort vs. Case-Control Diagnostic Accuracy Study Designs

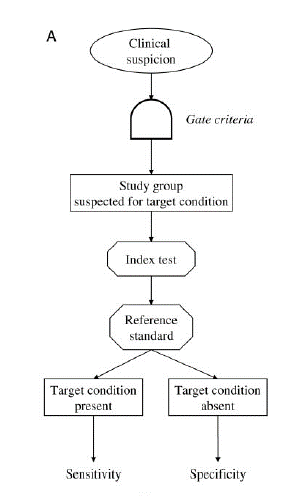

The diagnostic accuracy cohort study is the ‘traditional’ study design most of us think of for a diagnostic test accuracy study. In a cohort study, patients are at risk of a disease but undiagnosed at time of enrolment and then have the diagnostic test (index test) and the gold standard (reference standard) performed.

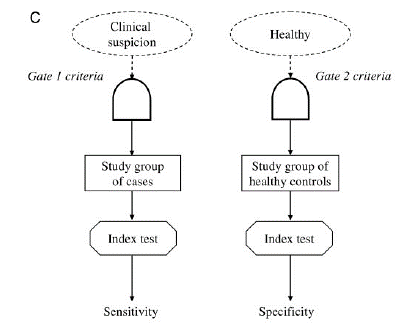

In a case control study, the disease status of the patient is already known and then the index test applied. For example patients with confirmed cancer on biopsy and healthy controls are divided into two groups and then the accuracy of a novel blood biomarker is studied.

So what’s the big difference? On the surface, they seem very similar but the use of a case-control study can significantly overestimate the diagnostic accuracy of a test. Here’s why.

Image from Rutjes et al. 2005

The issue of unmeasured confounding

The reason why case-control studies can overestimate diagnostic accuracy is that they are sampling patients from two different populations: one with the disease and one without. This contrasts with cohort studies that take the sample population at risk of the disease, and then later learn the true diagnosis.

There are 3 main reasons why case-control studies can overestimate diagnostic accuracy 1) severity of target condition in diseased individuals 2) alternative conditions in non-diseased individuals 3) the presence of comorbid conditions in either diseased or non-diseased individuals.

Severity of the target condition

Most diagnostic tests perform better in patients with severe disease (e.g. MRI is more accurate for large tumors than small ones). Thus, the selection of cases in a case-control study design can significantly impact the diagnostic accuracy of the test. (e.g. if severe disease cases are chosen this will overestimate the test accuracy). This is also known as spectrum bias, a bias arising from when a test is studied in a population with different disease severity than intended clinical use. In general, studying a test with a broad range of disease severity (from mild to severe) enhances the validity of a diagnostic test accuracy study.

The presence of alternative conditions in non-diseased individuals lowers diagnostic accuracy

When performing a diagnostic case-control study you select a control group that does not have the disease. By identifying patients without the disease, this may select for patients with different comorbidities than diseased patients. For example, say you are developing a new test to look for heart failure. There may be other conditions (e.g. coronary artery disease) that cause false positives. When you select a control group that doesn’t have heart failure, you might inadvertently choose patients that don’t have coronary artery disease as well (as the two often go together). When your test is studied in real-world setting, this additional confounder will lower the accuracy of your test.

The presence of comorbid conditions reduces diagnostic accuracy

Comorbidities have the potential to reduce the specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic tests. When a ‘cohort’ study is performed, all patients come from the same population of patients at risk of a disease, and thus have more balanced comorbidities. In a ‘case-control’ study, we choose the cases and controls ourselves from different populations with different comorbidities. This practice can lead to an overestimation of test accuracy.

Key Take Homes

So why should we care about how a diagnostic accuracy study is designed? Early phase diagnostic accuracy studies often employ ‘Case-Control’ study design as they are cost effective and can demonstrate biological feasibility. Unfortunately, these do not reflect the application of the diagnostic test in clinical practice. When deriving accuracy estimates for use in clinical practice, focus on studies that use a ‘cohort’ study design to avoid overestimating test accuracies.

Huge credit to the authors of “Case–Control and Two-Gate Designs in Diagnostic Accuracy Studies” for many of the concepts discussed in this posts – I highly recommend reading the full article here for an even deeper dive. https://academic.oup.com/clinchem/article/51/8/1335/5629913